Taurepang

- Self-denomination

- Pemon

- Where they are How many

- RR 849 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Venezuela 27157 (INE, 2001)

- Linguistic family

- Karib

The majority of the Taurepang are found in the Venezuelan savannah. Those living on the Brazilian side of the border with Venezuela and Guyana are found in villages within the Terras Indígenas São Marcos and Raposa Serra do Sol, living alongside indians from other ethnic groups. Since the early decades of the 20th century they have been under pressure from the expanding cattle ranching frontier on the high plains of Roraima. The presence of non-indians on their lands intensified with the construction of the BR-174 highway in the 1970s cutting across the TI. In 2001 an electricity transmission line was also constructed alongside the highway. In exchange the indians saw the ranchers relocated, but continue to live with the problem of having the seat of the municipality located inside the TI.

Name and language

The Taurepang refer to themselves as Pemon, a term meaning ‘people’ or ‘us’. Although little known in Brazil, this ethnonym is much more frequently used in Venezuela for the large Karib-speaking indigenous population. A. B. Colson (1986:74) states that in the frontier region between Venezuela, Brazil and Guyana there exist two major ethnic groups: the Pemon and the Kapon. The former is the self-designation of the Arekuna, Kamarakoto, Taurepang and Macuxi, and the latter of the Ingarikó and Patamona.

These terms are often used interchangeably such that, according to circumstances, a single group can be referred to as Taurepang or as Arekuna. The latter term appears to have a broader application and is frequently applied to all the groups inhabiting the Venezuelan savannah.

Various authors affirm that the indians themselves are unaware of the significance of the term ‘taurepang’, nor were my informants able to provide any explanation in this respect. However Brother Cesáreo de Armellada (1964:7), a Franciscan missionary who has worked among the Taurepang in Venezuela since the 1940s suggests that Taurepang is a word comprised by tauron ‘to speak’ and pung ‘wrong’, implying that the Taurepang are ‘those who speak the Pemon language incorrectly’, making this a pejorative designation coined by their neighbours.

Location and population

On the Brazilian side of the border the Taurepang are found in the northern part of the region of grasslands and mountains in the state of Roraima in the border region between Brazil, Venezuela and Guyana. They have as neighbours the Karib-speaking Macuxi and Akawaio (better known in Brazil as the Ingarikó) and the Arawak-speaking Wapixana.

In Venezuela the group (there known as the Pemon) occupy the so-called Gran Sabana, corresponding to the southeast part of the state of Bolívar. The Pemon territory covers the upper part of the Caroni river basin including the Carrão, Uriman, Tirika, Icabaru, Karuai, Aponguao and Surukun tributaries. On the headwaters of the Caroni (here known as the Kukenã) the Pemon villages are distributed along the Uairen, Arabopo e Yuruani rivers.

As well as the village existing within the Terra Indígena (TI) Raposa Serra do Sol, in Brazil there are Taurepang villages within the TI São Marcos, demarcated by Funai in 1976 and sanctioned by Presidential Decree 312 of 29/10/1991. It is made up of a stretch of land totalling 654,110 hectares bounded to the west by the Parimé river and to the east by the Surumu and Miang rivers. In its north-south direction it begins at the confluence of the Tacutu and Uraricoera rivers, where they form the Rio Branco, and extends as far as the Brazil-Venezuela border.

In the villages within the boundaries of the TI São Marcos there live three of the four existing indigenous groups of the Roraima high plains (‘lavrado’). The exception is the Ingarikó who are located near the frontier with Guyana. The indigenous population in the TI is made up by the Taurepang, Macuxi and Wapixana ethnic groups.

The TI São Marcos is crossed by a paved federal highway, the BR-174, which connects Manaus to Boa and then to the border with Venezuela. It is here that the seat of the municipality of Pacaraima is located, founded by the state of Roraima inside the TI and with a predominantly non-indigenous population that in 1998 was close to 2,000 people. Accompanying the highway are the metal towers and high tension cables bringing electricity from the Guri complex in Venezuela to Boa Vista.

The northern portion of the TI, where the Taurepang population is concentrated, falls squarely within the area of influence of the BR-174 highway, the Guri transmission line and the municipal seat of Pacaraima, making it a transit corridor between Boa Vista and Santa Elena in Venezuela.

Villages

With regard to settlement distribution, the majority of the Wapixana population is concentrated in the southern and central portions of the Terra Indígena, whilst the Taurepang population is found exclusively in the northern part. The Macuxi, who in 2004 represented more than 60% of the total population, are spread out across the whole area. There are high levels of Macuxi-Wapixana inter-marriage, followed by a much lower level of Macuxi-Taurepang inter-marriage. Marriages between Wapixana and Taurepang are very rare, almost certainly for no other reason than geographic distance.

During the period 1988-98 nine new villages were established from north to south in São Marcos. This confirms the mobility and dispersion that characterizes the settlement practices of these groups, as well as significant demographic growth.

History

Arekuna or Jarekuna were the ethnonyms by which the Taurepang were referred to by those who left written records over the course of the 19th century. They occupied a region that was the object of competing colonial interests and were dispersed among different nations: from the Amajari river in the basin of the Rio Branco, then the Empire of Brazil, to Mount Roraima, the point where the borders of Brazil, Venezuela and British Guiana met and the watershed separating the Amazon, Orinoco and Essequibo basins; on the other side of the Pacairama range they also occupied part of the Venezuelan savannah.

Given their frontier location, the history of contact with the Taurepang has been characterized to the present day by the advance of different expanding frontiers. A first phase of contact with the indigenous peoples of the Rio Branco basin began at the end of the 18th century with the establishment by the Portuguese colonial government of indigenous settlements in the region. This enterprise was short-lived, with the eruption in 1790 of a large-scale uprising by the forcibly settled indigenous population. Following the acknowledgement of the failure of the settlement policy, in 1787 the governor of the Capitania de São José do Rio Negro introduced the first heads of cattle into the region as an alternative colonization strategy, since the grasslands of the upper Rio Branco were, from a Portuguese perspective, particularly suitable for cattle raising by providing natural grazing. The ‘Fazenda do Rei’ was thus established. Two further ranching enterprises were subsequently established, although the dates in question are not clear. At first these were private enterprises, but they subsequently came under the control of the state.

From the 1840s onwards the border dispute with British Guiana would focus the attention of the state on the Rio Branco region, and especially on the question of the ‘fazendas nacionais’. The limits of one of these ranches, the so-called Fazenda Nacional de São Marcos, coincide exactly with the limits of the current Terra Indígena São Marcos, whose area, together with the other two properties, cover the grasslands of the upper Rio Branco region almost in their entirety. The area did not consist therefore of untitled land, but of large estates belonging to the federal government, whose interest in them lay in the fact of their being located on a disputed border.

There is no trace of the presence of civilian settlers in the region prior to the 1880s, after which the consolidation of cattle ranching took place, spurred by the wave of migration caused by the droughts in the Brazilian Northeast. In the brief period between 1877 and 1885 the number of head of cattle tripled to reach twenty thousand. The number of private ranches along the right banks of the Branco and Uraricoera rivers also multiplied, to the detriment of the Fazendas Nacionais. The practice of extensive cattle raising adopted in the region, with herds left to roam free and where ranches were not fenced, thus facilitating cattle rustling, lent itself to the creation of innumerable private herds (Koch-Grunberg, 1924).

The Jarecuna (or Taurepang) were seriously affected by the growth of ranching and, like their Macuxi and Wapixana neighbours, provided the labour required to work the ranches. Indigenous labour thus became a essential element for the consolidation of the cattle raising economy of the region since, as well as providing herdsmen to manage the cattle, it was indigenous labour that rowed the boats that constituted the communication between the upper Rio Branco grasslands and Manaus (Farage e Santilli, 1992). This was the background to the first wave of migration of indians from the Rio Branco region to neighbouring countries which intensified from the 1930s onwards.

The SPI and the Fazenda São Marcos

This was the situation when the Serviço de Proteção aos Índios (SPI), the official indigenous affairs agency during the years 1910 to 1967, arrived on the scene. In 1912 it sent an employee to the area lying between the Maú, Tacutu, Surumu and Cotingo rivers (Zany, 1914a). The official reported that the main demand the indians made to the newly-established Inspetoria do Rio Branco was the demarcation of their lands, by now suffering high levels of encroachment, above all in the Amajari river region, where the SPI now concentrated its activities.

Responsibility for the Fazenda São Marcos was transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture, where it came under the administration of the Superintendência da Defesa da Borracha (rubber protection board). When this was abolished in 1915, responsibility for maintaining São Marcos fell to the SPI. Within the boundaries of the property lay part of the Taurepang territory (between the upper courses of the Surumu and Amajari rivers), several Macuxi villages (located on the middle Surumu), as well as part of the Wapixana territory (in the region of the confluence of the Tacutu and Uaricoera rivers). Small portions of three large territories previously extending beyond national boundaries thus ended up being brought together as one.

The activities of the SPI became more consistent with the creation of an indigenous post at the headquarters of the property. Under its new administration the property received a series of improvements and the herd grew considerably. During the period from 1915 to 1930 a series of investments were made, including efforts to survey and demarcate the property (1920); health services (combating the 1920 bilious fever epidemic); the creation of an Indigenous Agricultural School (which in 1920 had 31 students); the Teófilo Leal Indigenous School (1924); innumerable improvements in infrastructure and growth of the herd (1924); and attempts to restore regular river communication between São Marcos and Manaus (1928).

By these actions the SPI inspector hoped to directly influence the specific land occupation regime of the Taurepang, Wapixana and Macuxi, traditional occupants of the São Marcos area. One of the guiding principles of the SPI constitution was the expectation of training and disciplining indian labour, transforming indians into ‘workers for the nation’ who would protect these distant frontiers.

From the 1930s onwards however we can detect signs of decadence in the activities carried out by the SPI. At the beginning of the decade claims of rustling and the disappearance of cattle from distant parts of the property resurfaced. In the 1940s there were the first reports of a new economic activity being undertaken on the São Marcos grasslands: contraband of goods over the Venezuelan frontier, where the government had established the town of Santa Elena.

Over the next decade the size of the herd continued to drop and the property to decline, according to an employee of the Manuas SPI inspectorate: “the victim of total pillage, with thousands of cattle having gone to start up numerous private ranches. Thus this important national asset has been looted and dissipated under the helpless, and also without doubt complicit, eyes of the authorities” (Lage, 1956). It is clear that by the time of the abolition of the SPI in 1967 this situation had not changed, and had probably got even worse. The SPI was therefore unsuccessful in its attempt to prevent the usurpation of the lands of São Marcos. The history of contact with the groups existing there has thus been characterized more by the growth of ranching than by the comforting dream of establishing indigenous agricultural settlements. The use of indigenous labour on the ranches and the growth of oppressive relations with ranchers became the emblem of local indigenous history. There are past episodes, remembered to this day by the indians of São Marcos, of the expulsion of whole villages by ranchers establishing their properties.

Funai and the BR-174 highway

In 1969 an early administrative measure of Funai was to transform the fazenda into the ‘Colônia Indígena Agropecuária de São Marcos’. Despite the use of the term ‘colony’ the Fazenda São Marcos continued to operate for the exclusive use of its resident indian population. However a new type of intrusion was occurring at the time. It was the time of road building in the Amazon and the BR-174 highway, linking Manaus to Boa Vista and then on to the border with Venezuela, had entered the area of the fazenda after crossing the Parimé river. It ran for 66 kilometres through the area, more precisely through its northern portion where the grasslands end and the forest begins, where the land is most fertile and where the Taurepang were concentrated.

At the end of the 1980s the National Security Council, through the Calha Norte project, started becoming heavily involved in government indian policy. It suggested the transformation of the lands inhabited by supposedly acculturated indigenous populations into ‘colônias’ [agricultural settlements], thereby allowing the populating of the country’s northern borders. São Marcos was clearly the strongest candidate for such a change of status, not least because it already contained the word ‘colônia’ in its name, had witnessed the growth within its boundaries of the town of Pacaraima at the far end of the BR-174 on the Venezuelan border, and had seen the arrival of new occupants who had settled along the edges of the highway. In addition, as the Colônia Indígena Agropecuária, São Marcos had experienced the loss of a portion of about a thousand hectares of its area on the border to the establishment of an army post in 1975, the physical demarcation of the area in 1976 and the first systematic survey of non-indian occupants in 1979 (Funai files 434/90 and 2504/79), as well as the growth and worsening of the conflicts with illegal occupants arriving mainly as a result of the construction of the highway.

The total number of illegal occupants recorded in 1979 was 91; by 1995 this had grown to 106. As we have seen, there have been two distinct expanding frontiers leading to the outside encroachment onto the lands of São Marcos: one beginning at the end of the 19th century and which grew over the course of the following decades with the occupation of the Parimé and Surumu river basins by cattle ranches; and a second phase beginning in the 1970s with the opening of the BR-174 and the wave of agricultural squatters who settled along the edges of the highway. In other words, a first ranching frontier, river-based and affecting the southern and central parts of the area; and a second agricultural intrusion, by road and affecting the northern portion. Both counted on the explicit support of the local state authorities – in the first case, this involved the state of Amazonas and in the second the former Federal Territory of Roraima (Funai file 2504/79).

Between 1995 and 1996 the government of Roraima upgraded the town of Pacaraima to a municipality, investing in its infrastructure and attracting more families through the distribution of plots of urban land. During this period the governor of Roraima, Ottomar de Souza Pinto, dedicated himself to legalizing the presence of the squatters by proposing a spurious agreement under which one side of the highway would be granted to the squatters and the other to the indigenous villages, an arrangement that ended up being accepted and which persists to this day.

The Guri transmission line and the removal of intruders from the TI

This was the situation when negotiations started with Eletronorte (Centrais Elétricas do Norte do Brasil) on the course of the transmission line bringing electricity from Guri. In April 1997 Eletronorte was granted authorization by the federal government to install an electricity transmission line connecting Boa Vista to the Guri hydroelectricity complex in Venezuela.

In developing the initial studies for the transmission line project, Eletronorte concluded that the most appropriate route for the line would be for it to be constructed alongside the BR-174 highway, cutting across the Terras Indígenas São Marcos and Ponta da Serra. At the same time as it undertook the necessary steps for the environmental licensing of the projects, through its indigenous affairs team Eletronorte took steps to begin a process of consultation and negotiation with the indigenous villages.

The negotiations on the course of the power line began in 1997 and it did not take long for a proposal to compulsorily acquire the ranches and remove intruders from the TI in exchange for permission to carry out the project to become the main item of negotiation.

Although they remained apprehensive about the consequences of constructing the power line so close to their villages, the pragmatism demonstrated by the indians in accepting the agreement was due to the situation in which São Marcos found itself: the demographic growth of the villages and the arrival of families from other indigenous areas on the high plains were regarded as factors that would lead to serious problems of space if the removal of non-indian intruders was not achieved. A further aggravating factor was that the principal development strategy in vogue amongst the indigenous population was to increase their herds of cattle.

High tension cables and metal pylons became part of the landscape of the region, though not without serious conflicts and negotiations between the affected indigenous populations, federal agencies and local authorities of both countries.

Eletronorte was responsible for funding the arrangements to compensate ranchers for investments made on the ranches and for a monitoring system that ensured the exit of around 110 squatters. The indians were also able to obtain the restoration of areas degraded by the construction of the electricity pylons and compensation for those that could not be restored because of their proximity to the line. In addition a number were individually compensated for damage to their private property.

The removal of intruders was achieved following a series of legal battles with the squatters. The process was made more difficult by the weak performance of Funai and by the local legal system which attempted to do a series of deals with the intruders. Although the negotiations started in 1997, the last rancher only left the area in April 2002.

On the Venezuelan side, the conflicts around the construction of the transmission line were much greater and delayed completion of the project by more than a year. The transmission pylons run for 80 kilometres from the Gran Sabana National Park and the Imataca forest in the state of Bolivar in southern Venezuela, home to more than fifty indigenous communities. Indians of the Pemon, Akawayo, Arawako and Kariña groups protested against the project and stopped construction on several occasions by bringing down pylons, blocking roads and demonstrating outside the Brazilian embassy in Caracas. Following lengthy negotiations, in January 2001 an agreement was signed between Fibe (Federação Indígena do Estado de Bolívar) and president Hugo Chavez. A joint committee was established with equal numbers of indigenous and government representatives to demarcate the indigenous areas and assess the impacts on the communities of mining, forestry and tourism activities in the region. The Venezuelan government also committed itself to not allowing the installation of public or private industrial projects in the communities without consulting the leaders of each group. It also created a permanent sustainable development fund to support indigenous community projects. Some months later, in August 2001, the Guri transmission line was finally inaugurated with the presence of the presidents of both Brazil and Venezuela.

Migration and preaching

In the first decades of the 20th century large numbers of Taurepang migrated across the border into Venezuela. Although the staff of the SPI attributed this exodus of indians from the Rio Branco area to the encroachment of ranching on their lands after 1914 [see the ‘History’ section], when we read the accounts of British naturalists we can see that these movements had already begun by the end of the 19th century, at the time of the emergence of millennial movements among the Carib peoples of the region, which led to the establishment of large villages on the Venezuelan side of Mount Roraima. Travellers who visited the region record the occurrence of dancing lasting throughout the night and the sacrificial offering of printed papers (cuttings from English language newspapers) distributed by the prophets and their followers.

Thus by 1880 several Arekuna, Akawaio, Macuxi and Patamona villages were swollen by new groups who gravitated to these sites in search of the new teachings of men whose prestige, thanks to their knowledge acquired at the British missions, extended throughout the region and had without doubt reached the Taurepang villages in the Rio Branco region. The growth of these cults marked the emergence of a religious movement that came to known as ‘Aleluia’, or Hallelujah. Born at the end of the 19th century among the Macuxi of the Rupununi river in British Guiana, it spread rapidly among the Akawaio, Patamona and Taurepang.

Butt (1960) suggests that the Taurepang would have heard of the new doctrine directly from the Macuxi on the trail connecting the high plains of the Rio Branco to Mount Roraima. In this case the paths of dissemination of the Aleluia among the Taurepang were identical to those of the first Adventist missionaries that reached the Taurepang villages of Mount Roraima on the Venezuelan side at the beginning of the 20th century.

To be precise, the Adventists began their incursions into the Venezuelan savannah to convert the Taurepang in 1911. In that year pastor O. E. Davis was preaching in the village of Kawarianaremong (or Kauarianá), near Mount Roraima; from 1926 to 1931, pastor A. W. Cott, accompanied by his wife, resided in the villages of Arapobo and Akurimã, where he built churches and began teaching the indians English. Both pastors had come to Venezuela from British Guiana.

Leader Jeremiah and pastor Davi Pacing

The village of Kauarianá was established during the final years of the 19th century and had as its leader Jeremiah, a follower of the Aleluia but also of the teachings of pastor O. E. Davis (known by the indians as Davi Pacing). This pastor, still remembered by many Taurepang groups, passed only a short period in the Mount Roraima region as he died soon after his arrival. There are several versions of the death of Davi Pacing. The Taurepang say that he was the victim of the witchcraft of the Ingarikó (the name currently used for the Akawaio, but which the Taurepang use as a general name for forest-dwelling indigenous groups). The so-called Ingarikó refused to give up polygamy, thereby rejecting the pastor’s teachings and killing him by sorcery.

The teachings of pastor Davis did not enjoy the same reception in Teuonok, the neighbouring village to Kauarianá. In contrast, the Taurepang inhabitants of Teuonok were extremely receptive to the catholic mission undertaken by father Cary-Elwes. According to Koch-Grunberg the relationship between the two villages was marked by ‘open enmity’. The rivalry between Teuonok and Kauarianá manifested itself by means of the different choices of their leaders. Whilst in Kauarianá Jeremiah fought to keep alive the teachings of the Adventist pastor, the inhabitants of Teuonok under their leader Skurumatá (a corruption of ‘schoolmaster’, according to several travellers), welcomed the Catholic priest.

Both villages were followers of the Aleluia doctrine before the arrival of the missionaries, but only the inhabitants of Kauarianá continued to practice this afterwards. Unlike those that adopted Catholicism, it seems that the Aleluia and the teachings of O. E. Davis, as conceived by the Taurepang, constituted doctrines that were mutually reconcilable. Thus the teachings of the pastor were incorporated into the millennial vision present in the region since the end of the 19th century in the guise of the Aleluia.

Pastor Cott and the consolidation of Adventism

After the death of O. E. Davis the Taurepang awaited the arrival of a new pastor, as he had foretold. However A. W. Cott arrived in the Mount Roraima region from Georgetown only in the second half of the 1920s, remaining until 1931 at the village of Akurimã, his main centre of activity.

The missionary teachings, combined with those of the prophets, captured the attention of an increasing number of Taurepang. Under the leadership of the tuxaua [chief] André, the village of Akurimã ended up attracting 900 individuals. Here the indians refused to work for expeditions arriving to explore the region and dedicated themselves almost exclusively to following André in the countless religious services he organized in accordance with the guidance of pastor A. W. Cott (Holdridge, 1931).

During this period, more precisely in 1927, the Border Inspection Commission under General Rondon arrived in the Rio Branco region. The Commission was divided into five groups to undertake the reconnaissance of the region, each responsible for surveying then little known rivers and frontiers. In addition to the group led by Rondon himself, who reached Mount Roraima and attempted without success to attract the Taurepang to the Brazilian side of the border, another group led by Lieutenant Tales Facó, following another itinerary and arriving in the village of Arabopo, located at the foot of Mount Roraima on the Venezuelan side, discovered a large concentration of Taurepang who had arrived from the Brazilian side. To the lieutenant’s surprise he found the missionary A. W. Cott established in the village and the figure around whom the indians congregated. Facó reported that more than 200 indians were preparing to open a large swidden garden for the express purpose of preparing for the arrival of Christ. The indians anticipated that the Saviour would lead them to a celestial paradise he had prepared for them.

In 1931 Cott was expelled by the Venezuelan government and the responsibility for catechising the indians of the ‘Gran Sabana’ was given to the Franciscan order, which proceeded to establish catholic missions at various places in the region (Salazar, 1978). According to several accounts, the Taurepang who were followers of Cott demonstrated strong resistance to catechism by the Franciscans and, soon after their arrival, the village of Akurimã broke up. The practice of Adventist rites was maintained by several groups who had had contact with Cott, as the oral tradition remembered as Papacá.

We can therefore conceive of the Taurepang migrations to Venezuela as a process resulting in part from the encroachment of ranching into the Rio Branco region. However we also need to take into account the emergence of a linked set of millennial movements among the Carib populations of the region from the late 19th century onwards and which caught the attention of those on the Brazilian side of the border.

Social organization

Among the Taurepang, just as among their Macuxi and Wapixana neighbours, we can observe a highly dispersed pattern of settlement, with villages generally located along secondary water courses. The movement of groups is intense and their knowledge of their territory is highly sophisticated. There is no geographical feature from streams to rock formations that will go unnamed.

Beyond the areas occupied by the villages there lives a veritable army of supernatural beings that fill up the adjacent spaces. This conglomeration composed of several classes of spirits, most of them malevolent, constitutes a set of mishaps that directly affects the mobility of the groups and thus the formation and breakup of villages.

The occurrence of established groups is not seen and social organization is based around bilateral kinship. The preferred marriage arrangement is between cross cousins (offspring of siblings of opposite sexes) and kinship terminology is of the Dravidian type. The domestic group (the nuclear or extended families) and the local group (the villages) are the two basic operative levels of organization. Neighbouring local groups form networks since they are linked by kinship ties and frequent contact. These organizational levels do not however imply a hierarchical political structure. On the contrary the villages are characterized above all by a strong degree of political autonomy.

In these societies there is a tendency to uxorilocal residence – the rule by which following marriage the husband takes up residence in his father-in-law’s house. This model of local group composition has as its main thread the relationships of alliance between a father-in-law leader and the men married to his daughters. The political stability of the group will depend on the nature of the relationship that unites the father-in-law and his sons-in-law. When the first grandchildren are born the decline of the village begins, culminating in the gradual return of the sons-in-law to their original families or the formation of new settlements. To this extent marriage between bilateral cross cousins brings greater stability to the local group since ruptures will rarely occur between related affines.

In any case the village is not a body that perpetuates itself over time independently of those who constitute it at any given moment. On the contrary, local groups demonstrate a relatively short cycle of existence such that the constant creation of new villages is a fundamental aspect of the social structure of these peoples. Removals, ruptures and regroupings make the villages of these peoples ‘historic events’ around which social memory is constructed. History is recounted according to a spatial record, emphasizing removals to new places or the return to old sites formerly inhabited (Rivière, 1984).

Cosmology

In the list of Taurepang oral traditions personal narratives, together with the myths whose theme is the exploits of the creator hero Makunaíma, are referred to as pandon, a term translated by the Taurepang as ‘stories’.

The events retold in the myths take place in a time the Taurepang call Pia daktai, a ‘time of origin’, when the earth, people and animals took on the shape they have today. In contrast, an individual narrative describing the narrator’s life and family are held to have happened ‘now’, sereware, indicating that they deal with events much more recent than those that occurred in the Pia daktai.

Changing from one type of narrative to the other does not obey any kind of rule. Nothing stops a narrator moving from an account of the exploits of Makunaíma in the region of Mount Roraima to another about a village situated in the same place when the narrator was young. There is a kind of compression of type as the narrative approaches the present, a time of greater detail and memories.

Makunaíma

The most important cycle in Taurepang mythology deals with the saga of the cultural hero Makunaíma, sometimes referred to as a single character, at others as a group of brothers, as for example in the account collected by father C. de Armellada (1964:32ss). In the ‘time of origin’ men and animals possessed human form, pemon-pe. Sharing with the other earthly beings a pre-social existence, the Makunaíma brothers, born out of the union between the sun Wei and a women made of clay, wandered in search of their father who had been captured by the Mawari, malevolent spirits living inside the mountains. In the Mount Roraima region they rediscovered their captive father who, once free of his captors, rose into the heavens leaving his children behind on earth.

The Makunaíma brothers remained wandering near Mount Roraima, following animals (amongst which the coati, akuri) in search of food. It was this animal that showed the hero the ‘tree of the world’, wadaka, from which they gathered all the edible fruits. Overjoyed with its abundance, in an act of immeasurable greed, Makunaíma felled the tree. Water spilled out of what remained of the trunk, causing a great flood. The deluge was followed by a great fire which destroyed men and animals. Following this cataclysm, Makunaíma created new men and new animals out of clay, giving them life (Koch-Grunberg, 1924/1981, II:43; Armellada, 1964:60). The Taurepang recount that Mount Roraima is the root of the tree that remained after the great flood, pointing out that its shape is similar to that of a tree stump, despite its immense size.

Out of all the exploits of Makunaíma this is the episode most commonly referred to. In several others, the hero transforms the various beings he comes across into rocks. In the end Makunaíma departs eastwards, to the other side of Mount Roraima, leaving behind a world in which several of his exploits remain crystallized, principally in the rocky outcrops of the Taurepang territory. Afterwards Makunaíma never again interfered with mankind, leaving behind a sad legacy: the world to which mankind was confined no longer possessed the same nature as had lived before the felling of the great tree. The ‘now’ beings, sereware, lost the identity they previous had; they were no longer all Pemon. Thus changeability came into the world.

If before all things were people, pemon-pe to ichipue, after the great flood the different characters that appear in the pandon would differentiate themselves from mankind, occupying other domains and begetting new relationships with human beings, of an explicitly antagonistic nature.

Upatá and Taren

The Taurepang give particular emphasis to the notion of Upatá, representing the place of birth or residence. This notion, here translated as ‘my place’, corresponds to the village and denotes not simply the physical space, but a space that is above all social. Whilst a house is patasek, upatá means more appropriately ‘home’.

In the Taurepang territory there are places of illness, the enek-patá, and places that are good for the establishment of villages, the wakipe-patá. It is between these extremes, from the former in the direction of the latter, that groups migrate.

Although aware that they are surrounded by a highly varied set of hidden beings, the Taurepang are not always able to provide a complete list of them all. A more sophisticated understanding of these issues forms the territory of the shaman, as well as of a vast repertory of magical invocations known as Taren. In their day-to-day use, these invocations serve to cure simple illnesses for which the intervention of a shaman is not required, such as snakebites, small wounds, low fevers, diarrhoea and so on.

The taren appear to be based on events that took place in the Pia daktai. They act in opposition to those evils introduced into the world in this initial period by the cultural heroes. The Taren are therefore always introduced by a mythical tale that recounts the origin of the evil it seeks to counter. This is followed by a series of repeated phrases which ‘nominate’ an agent possessing the opposite nature to the disturbance the Taren aims to remedy.

Religiosity and Adventism

This here [heaven] our good place with Jesus, nobody sad, nobody tires working, there good place and the sun lighting up everything... and what a sun in our place. Here we are in the dark, there no dark, everything lit up, this will never end... the book tells everything (1988).

The 'darkness of the earth' makes sense to the extent that the terrestrial level hides, in many forms and in different features, several classes of supernatural beings only visible to shamans. They appear to men precisely during shamanistic rituals, when all is dark and nothing can be seen. Potentially aggressive and cannibalistic, these beings maintain a mutually predatory relationship with mankind. In this way, in contrast to an earth full of hidden dangers, there is a world where everything is visible, all is light.

Purification

Baptism is an event of the utmost importance to the Taurepang. In the ritual the 'body is washed' according to the Taurepang, removing Makoi from the body and leaving this in the care of Rato, an aquatic serpent below the waters. Those baptized emerge from the river as new people able to travel the road to heaven after their deaths.

Trapped on the earthly level, their social situation binds humans to permanent interaction with the spirits of the forest and the rivers, the domains from which food is obtained. But hunting and fishing constitute a form of 'robbery' of the children of the parents of each species or, in the case of fish, of the children of Rato. In the same way that the illnesses affecting humans are in the majority of cases the result of the theft of the souls of the victims by these beings. In such cases the intervention of the shaman is required. He will be responsible for restoring the sick person to health or for maintaining the balance in the relationship, constantly under threat, between the inhabitants and the world that encircles the village. It is this situation that turns people imatanesak: the consumption of game and the consequent need for shamanistic treatment that puts people into contact with the spirits of the dead and the Mawari.

Baptism is able to resolve this situation since it is accompanied by a series of food restrictions, above all the consumption of large animals and of caxiri [fermented manioc beer]. Thus whilst shamanistic cure consists of standing up to malevolent spirits, baptism has a preventative purpose.

We can thus see that, through baptism, prophetic religion appears as a counterpoint to a particular world with which hitherto only a shaman could interfere. The prophets thus offer a new relationship with this world, operating by means of elements similar to those of the shamans - words. Words that encapsulate knowledge of a domain representing the overcoming of present conditions.

From Makunaíma to Jechikrai

The adoption of Adventism by the Taurepang can be understood not as a simple catechistic imposition but, once its contents have been interpreted, as a doctrine that makes sense in terms of the Taurepang world view. Thus prophetic religion can be seen not as a response to adverse conditions resulting from contact, but as a solution to an internal dilemma of the society; that is to say, the impossibility of encountering a ‘good place’, an upatá, among the different domains of the earthly plane.

Thus, just as knowledge of the supernatural beings was restricted to the shamans and those trained in magic incantations (the Taren), knowledge of the celestial paradise became a monopoly of the prophets, the bearers of new words that, unlike the words pronounced in the Taren and which refer to the past (to the Pia daktai), evoke a future time. In an analogous way, as the shamanistic narrative focuses above all on the earthly level, the prophetic narrative concentrates on the celestial level. Therefore it is not the case that there is a radical opposition between prophets and shamans, since the visions of the prophets are reached through the same mechanisms as the shaman’s trances – through journeys of the soul.

It should be stressed that the celestial upatá is a place that has been prepared. Jechikrai (the Taurepang version of Jesus Christ) is charged with this task. His characteristics are thus diametrically opposed to those attributed to Makunaíma. The latter, following his journeys on the earth, left for the east (in other words, he departed horizontally) bequeathing a hostile world to humans. In addition his social behaviour was incorrect and excessive. On the other hand, he who the Taurepang call Jechikrai will arrive from above (in other words, moving vertically), ready to lead mankind to a place of total security. Good teachings for social harmony are also associated with him, together with measured behaviour, of which the food taboos are the best example. To summarize, just as the celestial paradise came to be conceived in opposition to the earth to which the Taurepang find themselves relegated, this new actor can only be understood to the extent to which he negates the attributes of the cultural hero Makunaíma.

A new meaning is thus given to the concept of upatá, relocating it on another plane, the beyond. Upatá is therefore the central notion by which the Carib peoples of the lavrado [high plains] region of Roraima have incorporated the teachings of the missionaries, crediting them with the form of prophetic movements. It is the place of full security, which the Taurepang try however precariously to adapt to the place where they actually live. Mankind’s erratic journeys through life, as well as the doubts that assail them at each resting place (where do we go now?) lead the Taurepang to believe that these movements are not guided by a fixed destination. Abandoned by Makunaíma in a hostile world, the only thing that remains for the Taurepang to do is to believe in a new hero who, seeing their earthly suffering will focus on preparing a new place in heaven for them.

Economic activities

The central feature of the Taurepang economy, as well as of the other groups that inhabit the TI São Marcos, is a strategy that embodies the hope of successfully combining a traditional subsistence model with the intensification of market linkages.

In certain parts of the extreme north of the Terra Indígena, a forested area, there is a high availability of such game as agouti, tapir, coati, wild pig, monkey, deer, peccary, macaw, guan, curassow and tinamou. These resources are however not exploited as the two villages best placed to exploit them (Bananal and Nova Esperança) allege religious reasons (the Taurepang may not hunt large animals), lack of weapons and the fact they no longer use bow and arrow or blowpipe. In the rest of the area it is said that game is generally scarce nowadays, in contrast to the past when in certain places women were afraid to work in the gardens because of the numbers of wild pig.

In respect of fish it should be recalled that this area is located close to the Pacaraima mountains and contains the headwaters of tributaries of the Parimé e Surumu, as well as the sources of these rivers themselves. The greater part of the available resources is therefore small fish and minnows. According to several informants, in the past the Parimé was an important source of fish for the villages, but nowadays the supply is relatively small.

As a consequence the greater part of the animal protein consumed by the villages is the result of purchases from the butchers in the Vila de Pacaraima, where according to the indians, cattle is slaughtered daily.

Fruit gathered includes bacaba, inajá, taperebá, urá, ingá, bacuri, tucumã, açaí, patauá, castanha do mato, buriti and jenipapo. However these resources, as well as being seasonal and available only in small quantities, appear not to be much sought after.

One factor that has contributed to reducing hunting, fishing and gathering activities is the growing orientation of economic activities towards the commercial market of Pacaraima. For the local indigenous groups this implies increasing their efforts and the time devoted to producing agricultural surpluses that can be placed on this market.

Gardens and animals

Agricultural activities among the villages in the northern portion of the TI São Marcos are extremely diversified. Family gardens grow the following species: manioc, banana, maize, rice, beans, yam, taro, potato, squash, sugarcane, sweet manioc, papaya, watermelon and orange. The patios, areas of varying size around the house, are used to grow fruit trees: ingá, mango, cashew, lemon, tangerine, guava, peach palm, Amazon olive, coconut, soursop, cupuaçu, Brazil nut, rose apple, avocado, cotton, spiny andira, annatto, trumpet bush, orange, breadfruit, pineapple, genipap, sugar apple, lime and sweetsop. It should be noted that this high diversity of species grown on house patios refers to all the villages in the area, including Taurepang, Macuxi and Wapixana groups.

Generally speaking swidden gardens contain manioc, banana, maize, rice and beans. The first two are planted in much larger numbers in the expectation of commercial sale. The gardens are always individual and it is commonly said that past attempts to plant collective gardens were unsuccessful. Normally each family will have three gardens in different phases: one in full production, another being prepared and a third on the way to being abandoned. Preparing the ground for a new garden starts in January and continues until March. During this period the ground is hoed and the trees are felled, to be followed by burning. Planting occurs from May onwards and the harvest takes place the following year. Like gardens, raising chickens, pigs and sheep is carried out individually and is widespread. Despite the introduction of these animals, the Taurepang diet continues to be based around damorida, a pepper stew made with leaves of the bush known as aurossá, cooked together with the meat, and beiju [unleavened manioc bread].

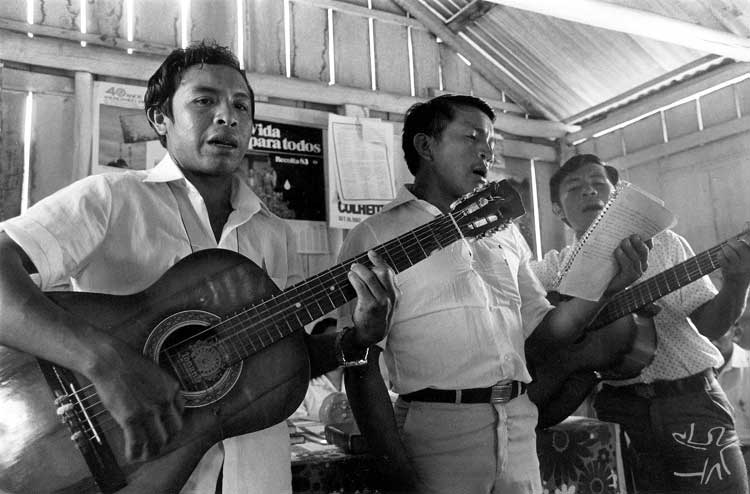

The shed where the manioc is processed is used on a daily basis by families taking turns throughout the week to prepare beiju and farinha [manioc flour]. The typical sound heard in the afternoon in the villages is the noise of the small motor turning the manioc grater, combined with the singing of children practicing for the services of worship. At the end of the afternoon the women go from house to house with pans of damorida and handfuls of beiju to be consumed at the frequent collective meals where the Taurepang meet for lively and informal conversations before retiring for the night.

Trade

Trade in agricultural products and the purchase of goods that nowadays involve the villages of the northern part of the TI São Marcos take place almost exclusively in Pacaraima. The main products sold by the villages are banana, farinha, beiju, manioc starch and tapioca. Proximity to the highway and the availability of transport determine to a large degree the level of commercial activity each village engages in. On Fridays there is a street market in the town and this is the opportunity for the indians to sell their produce.

In the northern sector in 1998 there were 54 pensioners and at least one salaried teacher in each village. In order to acquire more expensive items such as clothes and footwear, indians increasingly frequently look for temporary work as building or agricultural labourers. Such purchases are generally made in the Venezuelan town of Santa Elena where prices are lower.

Cattle

It is frequently said in the villages that, if there is one thing the indians of the Roraima high plains have learned over the course of more than two centuries of contact, it is how to manage cattle. In nearly every village the cattle are differentiated: there is a collective herd and an individual herd. The latter is the sum of all the cattle belonging to each domestic group that makes up the village.

The creation of an individual herd begins when the village receives cattle. A herdsman is immediately chosen from among the men of the village and is responsible for looking after the cattle. He is paid a ‘quarter’, receiving one out of every four newborn calves to start his own herd. As the job of herdsman is held in rotation by each man in the village, after a few years everyone will be the owner of a part of the overall herd.

Notes on sources

For a detailed ethnography of Taurepang society I recommend to the reader the works of D. J. Thomas (1971, 1972, 1973, 1976, 1982 e 1983). Thomas is an American anthropologist who undertook fieldwork among the Taurepang groups in Venezuela at the beginning of the 1970s. There is also the 1912 study of the German ethnographer T. Koch-Grunberg which, in addition to providing a detailed description of Taurepang society, also contains his field diary of indisputable historic importance. Similarly the travel journal of the English Jesuit K. Cary-Elwes, who made two visits to the Taurepang villages of Mount Roraima in 1912 and 1916, provides important details of the rivalries among the various Taurepang leaders of the region.

My master’s dissertation (1993) seeks to contribute to a better understanding of the history of this society, in particular of those groups located on the Brazilian side, in the upper Rio Branco basin. It examines ranching activities on the upper Rio Branco grasslands and the growth of the various millennial movements among the Macuxi, Akawaio and Taurepang groups living around Mount Roraima. I have tried to verify the extent to which each of these factors enables an understanding of the migrations of the Taurepang into Venezuela.

In 1998 I prepared a report on the history and overall situation of the Terra Indígena São Marcos, under contract to the Assessoria Indigenista of Eletronorte and within the framework of the Brazil-Venezuela Electricity Interlinkages project.

Finally, in 2003 Gabriela Copello Levy submitted her master’s dissertation Vozes Inscritas: o movimento de San Miguel entre os Pemon, Venezuela to the University of Campinas (Unicamp).

Sources of information

- ANDRELLO, G. 1993a : Os Taurepáng: Memória e Profetismo no Século XX. Dissertação de Mestrado, UNICAMP.

- -------------1993b : “Rumo Norte: Migrações e Profetismo Taurepáng no Século XX”. Ciências Sociais Hoje 1993:244-265.

- BARBOSA, R. & Ferreira, E. J. G. 1998 : “Historiografia das expedições científicas e exploratórias no vale do rio Branco” in Barbosa, R., Ferreira, E.J.G. & Castellón, E.G. (orgs) Homem, Ambiente e Ecologia no Estado de Roraima. Manaus: INPA.

- CHAUVIN, C. E. 1941 : “Ofício ao Coronel Vicente de Paula Teixeira da Fonseca, Diretor do Serviço de Proteção aos Índios”. Documento Manuscrito do Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.

- COUDREAU, H. 1887 : La France Equinoxiale, Tomo II. Paris: Chalamel Ainé Editeur.

- Documentos sobre as Fazendas Nacionais. Documento manuscritos (No 16, Lata No 197) do Arquivo do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro.

- FARAGE, N. 1986 : “As Fazendas Nacionais do Rio Branco”. Datilo. São Paulo: CEDI.

- ------------- 1997 : “Os Wapixana nas fontes escritas: histórico de um preconceito” in Barbosa, R., Ferreira, E.J.G. & Castellón, E.G. (orgs) Homem, Ambiente e Ecologia no Estado de Roraima. Manaus: INPA.

- -------------. & Santilli, P. 1992 : “Estado de Sítio: Territórios e identidades no vale do rio Branco” in Carneiro da Cunha, M. (org) História dos Índios no Brasil. São Paulo: FAPESP/Secretaria Municipal de Cultura/ Cia das Letras.

- -------------. 1991 : As Muralhas dos Sertões. Os povos indígenas do rio Branco e a colonização. São Paulo: ANPOCS/Paz e Terra.

- FARIA E SOUZA, T. 1931 : “Relatório apresentado à Inspectoria do Serviço de Proteção aos Índios do Amazonas e Acre”. Documento Manuscrito do Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.

- FIUZA, J. G. 1941 : “Relatório ao Sr. Major Carlos Eugênio Chauvin, Inspetor do Serviço de Proteção aos Índios do Amazonas e Acre”. Documento Manuscrito do Documento Manuscrito do Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.

- GONDIN, J. 1922 : Através do Amazonas. Manaus

- Instituto Socioambiental 1996 : Povos Indígenas no Brasil 1991-1995. São Paulo: Instituto Socioambiental.

- KOCH-GRUNBERG, T. 1924/1983 : Del Roraima al Orinoco. Caracas: Ediciones del Banco Central de Venezuela.

- LAGE, A . E. 1956 : “Relatório sobre o território do Rio Branco”. Documento Manuscrito do Documento Manuscrito do Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.

- LEMOS, B. M. P 1918 : “Memorial dirigido ao Procurador Geral da República”. Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.

- LIMA, A. C. de S. 1985 : Aos fetichistas, ordem e progresso: um estudo do campo indigenista no seu estado de formação. Dissertação de Mestrado, Museu Nacional.

- OURIQUE, J. 1906 : O Valle do Rio Branco. Manaus: Edição Oficial.

- PEREIRA, L. 1917 : O Rio Branco – Impressões de Viagem. Manaus: Imprensa Pública.

- Funai 1979 : Processo 04255/79 – Relatório do sistema de criação bovina. DGPI. (manuscrito)

- Funai 1979 : Processos 2504/79 – Encaminha levantamento dos ocupantes da Área Indígena São Marcos no Território Federal de Roraima. (manuscrito)

- Funai 1990 : Processo 434/90 – Homologação da demarcação topográfica da Área Indígena São Marcos. DID/SUAF. (manuscrito)

- RIVIÈRE, P. 1972 : Cattle Ranchers in Forgotten Frontier. Londres: Holt & Leenhart.

- ----------------. 1984 : Individual and Society in Guiana. Cambridge University Press.

- SANTILLI, P. 1989 : Os Macuxi: História e Política no Século XX. Dissertação de Mestrado, UNICAMP.

- ----------------. 1997 : “Ocupação territorial Macuxi: aspectos históricos e políticos” in Barbosa, R., Ferreira, E.J.G. & Castellón, E.G. (orgs) Homem, Ambiente e Ecologia no Estado de Roraima. Manaus: INPA.

- SPI, 1915-1930 : “Relatórios da Inspetoria Regional do Amazonas e Acre”. Documentos Manuscritos do Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.

- STRADELLI, E. 1889/1991 : “O Rio Branco” in Naturalistas Italianos no Brasil. São Paulo: Ícone/Secretaria Estadual de Cultura.

- THOMAS, D. 1982 : Order without governement: The society of the Pemon indians of Venezuela. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- URBINA1986 : “Some aspects of the Pemon system of social relationships”. Antropologica 59-62:183-198.

- VIVEIROS DE CASTRP, E 1987 : “Sociedades Minimalistas: A propósito de um livro de P. Rivière”. Anuário Antropológico 85, Rio de Janeiro: Tempo Brasileiro.

- ZANY, J. A . 1914a : Memorando de J.A.Zany ao Sr. Cap. Alípio Bandeira”. Documento Manuscrito do Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.

- ---------------- . 1914b : “Relatório de J. A. Zany”. Documento Manuscrito do Setor de Documentação do Museu do Índio/Funai, Rio de Janeiro.