Xipaya

- Self-denomination

- Where they are How many

- PA 241 (Siasi/Sesai, 2020)

- Linguistic family

- Juruna

The Xipaya were persecuted by the colonizers the 17th century onwards and forced to work in extractivism. They were relocated to the Tauaquara Mission in the region where the town of Altamira later flourished and where they were always marginalized and their indigenous rights denied. Today they are distributed between this town and the villages and are fighting for their territorial rights and citizenship.

Name

The Xipaya name is related to a type of bamboo used to produce arrows, according to the people themselves. The qualities of this grass, which has a strong but flexible stem and exuberant vegetation, is compared to those of the group itself. Nimuendajú (1948) notes the various forms of writing the name found in the literature: Juacipoia, Jacypoia, Jacypuiá, Juvipuyá, Acypoia, Achupaya, Sipáia, Achipaye, Axipai, Chipaya and, in the most recent documents produced by FUNAI and CIMI, Xipaya and Xipaia.

Language

The Xipaya form part of the Juruna linguistic family from the Tupi trunk. Three languages are included in this family: Manitsawa (extinct), Juruna and Xipaya. In 1995 the Xipaya language was studied in the doctoral thesis “Estude Morphosyntaxique de la Langue Xipaya” by Carmem Lúcia Rodrigues. Most of the Xipaya today speak Portuguese, though some older people in the city of Altamira still know how to speak the language, but do not do so on a daily basis.

Since their history includes a period when they were forced to migrate to Mebengokre lands, many of them know how to communicate in the Kayapó language (Ge trunk), however this is not a routine practice.

Location

The Iriri and Curuá rivers in Pará state comprise an affluent and subaffluent respectively of the Xingu river, forming part of its hydrographic basin whose headwaters lie south in the state of Mato Grosso. The Xipaya can be found in the Xipaya Indigenous Territory on the shores of the Iriri and Curuá, as well as in the city of Altamira and in Volta Grande do Xingu.

The Xipaya Indigenous Territory (IT) is currently in the process of being registered. A demand for recovery of part of the territory was presented to FUNAI in a letter dated May 9th 1995. A Working Group was sent by the latter agency to undertake field studies on October 29th 1999, in order to collect basic information on the area claimed by the Xipaya. The first part of the work, finished in April 2002 and composed of the identification and demarcation study and survey, concluded that the registration process should proceed within the boundaries proposed in the Detailed Identification and Delimitation Report for the Xipaya Indigenous Territory.

The IT includes Tukamã village and three smaller communities. The village is bisected by the João Martins creek and is located on the left shore of the Iriri river. Its population is composed of seven families that totalled 33 individuals (data from 1999). The village is circular in form, a layout borrowed from Mebengokre architecture, the result of years of living in close proximity. It possesses a meeting house in the centre, a football pitch, houses and a school. Located beyond the circle are the health post, two houses, an artesian well and a community swidden. Yards contain fruit trees, vegetables and medicinal plants.

The three communities are: Nova Olinda, the oldest settlement, located on the left shore of the Iriri river with 19 people distributed in three houses; Remanso, situated on the left shore of the Curuá river with five individuals; and São Geraldo, located on the right shore of the Curuá with a single house and swidden.

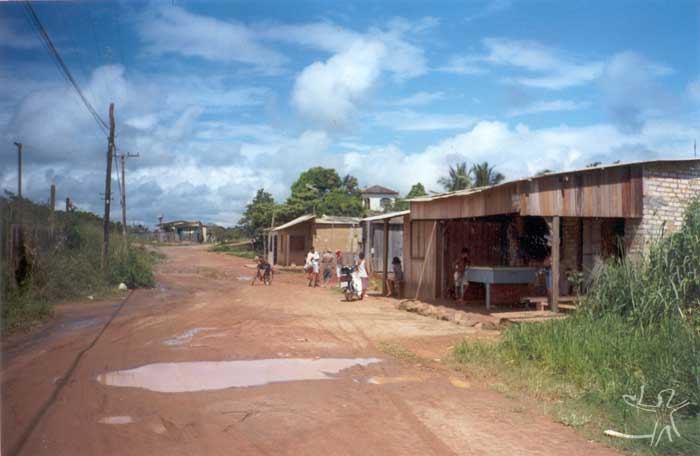

The largest number of Xipaya live in the city of Altamira, an outcome of the Tauaquara mission founded by the Jesuits and the different periods of migration prompted by fleeing the conflicts and diseases on the Iriri and Curuá rivers, as well as by marriages to non-Indians. In the city kinship ties with the Kuruaya are more evident due to the ease of visiting and meeting to dance. The Xipaya population in Altamira corresponds to 44% of the indigenous population; the Kuruaya account for 36%, the Juruna 7.97%, Mebengokre 5.8%, Arara 1.45%, Karajá 1.45% and others 2.9%.

Two Xipaya communities exist in Volta Grande do Xingu: Jurucuá and Boa Vista, composed of just two families.

History of occupation and contact

Nimuendajú (1948:219) mentions the hypothesis that the original Xipaya homeland was located on the headwaters of the Xingu river. The skill in building and navigating ubás (flat-bottomed canoes) allowed them to travel along the river’s tortuous routes and reach its right-shore affluents, the Iriri and Curuá.

The oldest colonial occupations on the lower Amazon and the mouth of the Xingu occurred around 1600 and were realized by the Dutch, Irish and British who founded various trading posts.

The Dutch took control of the fertile shores of the Xingu river, making sugar cane plantations and building a fort at its confluence with the Amazon close to the villages of the Mariocais. In 1620 the Portuguese destroyed these positions with expeditions commanded by Pedro Teixeira and other explorers. The Xipaya managed to resist for a considerable time, a fate not shared by other indigenous groups who lived in the region of the Iriri/Curuá/Xingu rivers, such as the Kuruaya who were encountered a few years after the occupation of the lower Amazon around 1685.

From the 17th century onwards the Xipaya were mentioned by the anthropological literature, in the writings of priests, travellers, scientists and presidents of Pará Province. The first sustained attempt at contact was led by Father Roque Hunderfund during his incursion along the Xingu river and its affluents as part of his work of converting the Indians and establishing missions. Hunderfund’s arrival in 1750 was a watershed in the ethnohistory of the peoples who lived in the region of these rivers. The establishment of the Tavaquara or Tauaquara mission on the shores of the Xingu river very close to what would become the town of Altamira in Pará prompted the first spatial and socio-cultural split involving the Xipaya, Kuruaya, Juruna and some of the Arara.

The report of the president of Pará Province, Francisco Araújo Brusque (1863), recognizes the vulnerable situation of the Indians where he mentions the Xingu region and its inhabitants. The report reveals the colonist’s sparse knowledge of the region with the physical appearance of the Indians outweighing any description of their character:

There are thirteen wild tribes inhabiting those parts, which may well be the most fertile of this province: the Juruna, Tucunapenas, Juaicipoia, Urupaya, Curiaias, Peopaias, Taua-Tapuiara, Tapuia-eretê, Carajá-mirim, Carajá-Pouis, Arara and Tapaiunas. To pick out the ethnic group in question, the Juacipaias, the tribe is reduced in number and currently contains sixty individuals. They are divided into small groups inhabiting four huts, situated on the islands found on the cited Iriri river. They obey a tuchána named Vacumé and possess the same laughs and customs as the Juruna Indians who they are very much like, though they are more indolent and deformed...

Some exploratory expeditions undertaken on the Xingu river, including those of Karl von den Steinen (1841), Prince Adalbert of Prussia (1849) and Henry Coudreau, who also reached the Tapajós river (1895-96), mentioned the presence of both the Xipaya and the Kuruaya living in the region.

Between 1910 and 1913 Emília Snethlage, head of the Zoology Department of the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG), undertook various expeditions to the Xingu region. The researcher’s informants came from the Xipaya and the Kuruaya, which allowed her to update the knowledge of the contemporary contact situation of these two groups.

The ethnographer Curt Nimuendajú visited the Xingu, Iriri and Curuá rivers over the space of three and a half years and observed the contact situation experienced by the region's indigenous groups. The documents written by him state that the Xipaya were part of a large number of indigenous groups living on the lower and middle Xingu, such as the Juruna, the Arupaí (extinct), the Tucunyapé (extinct), the Kuruaya, the Arara and the Asuriní. The controlled the Iriri and Curuá rivers at the same times as they tried to stem the advance of the Mebengokre (Kayapó), Carajá and the invading rubber tappers.

The region’s ethnic groups were classified by Nimuendajú (1948:213) into three groups based on geographic criteria: the canoe groups, limited to the Xingu, Iriri and Curuá rivers (Arupaí, Xipaya and Juruna), groups that lived in the central primary forest (Kuruaya, Arara, Asuriní and Tucunyapé) and the savannah group (Mebengokre).

The occupation of the region and the contact between the Xipaya and national society around 1880 showed that the indigenous groups on the Xingu, Iriri and Curuá rivers had been squeezed on all sides. The incursion of the Mebengokre towards the mouth of the Xingu river, the Munduruku’s expansion eastwards and the Carajá’s expansion westwards, was compounded in the 19th century by the arrival of rubber explorers, who entered the region via the mouth of the Amazon and up the Xingu river, navigating along its affluents and leading to various encounters of different intensities, closing the circle surrounding the groups inhabiting the region.

Two points are important to consider in relation to contact: the relocation of the Xipaya to locations determined by the owner of the rubber area (seringal) and the forced assimilation of the regional social organization insofar as they began to form part of the routine sustaining the local economy.

The expansion of groups like the Mebengokre and Karajá continued in parallel with the advance of rubber extraction and the recruitment of the workforce for labour on the seringais, extracting rubber and Brazil nuts. Later when these products lost their market value, supplying the trade in big cat furs took over. This activity required knowledge of the region’s wildlife and landscapes that only the Indians possessed and the colonizers spared no efforts in keeping them in a condition of slavery. The adverse forces present in the region were capable of forging tenuous alliances and of destroying them. As a question of survival, the past and recent enemies organized themselves according to the situation. Hence Xipaya, Kuruáya and Mebengokre, once enemies, gradually found themselves obliged to live together in order to safeguard minimally their physical integrity.

Around 1885 the Xipaya were persuaded by the Mebengokre to retreat to the Gorgulho do Barbado, a site on the Curuá river that they abandoned around 1913 after a bloody clash with rubber tappers. Later, in response to the interests of the rubber bosses, there was a new split and some of the Xipaya were transferred to the lower Iriri and others to the Curuá river. In his writings Snethlage (1920b:395) mentions:

During the time when I was there, the Chipaya lived slightly above the site called Santa Júlia [on the Iriri river] while previously the Indians who had been working for Accioly lived below Santa Júlia... we also encountered them in almost all the colonies bordering the Iriri river, as well as on the lower Curuá... The number of Chipaya inhabitants and their descendents seems not to have been very high for some time and over the last few years has fallen even further, primarily because of the absorption of Indians into the colonizer’s workforce... It is estimated that there are still several hundred Indians in a phase of transformation from Indians properly speaking to tamed Indians. These peoples survive by hunting and fishing, while some work as canoeists. Only a minority live from rubber extraction. In the latter case, they do so from pure necessity, in order to acquire products that need to be bought rather than taken from the forest or rivers.

Snetlhage estimated that around 1918 the Xipaya numbered approximately 80 people. Nimuendajú estimated that in 1920 there were 30 individuals scatted across a large number of locations, such as Largo do Mutum and Pedra do Capim on the Iriri river, mixed with a few Kuruaya survivors.

In the 1940s-50s the Xipaya population was once again redistributed. During this period of contact, disease, death, marriage between the Xipaya, Kuruaya and Juruna and the north-eastern Brazilians arriving in the region as ‘rubber soldiers’ had already imprinted a new profile on the region. The successive forced relocations and the dispersion of the group gave the idea that the Xipaya had disappeared as an ethnic group.

In the 1970s the Xipaya began a movement that resulted in the group’s unification and the conquest of their former territory. The village on the Iriri was rebuilt around the family of Tereza Xipaya de Carvalho – married to a north-eastern farmer since 1951 with whom she had 22 sons. Afterwards they lived for some time in the farm colonies close to the city of Altamira and then moved to São Félix do Xingu with all their children and their respective families. Due to a series of problems with non-Indians in the town they went to live with the Mebengokre. At the invitation of their leader or cacique, Colonel Tutu Pombo, they worked as farmers for five years, as the Xipaya recall:

We lived in Kriketum with the Kayapó. The village was headed by Tutu Pombo, he always said that we had land on the Iriri. We didn’t live in the same village, we made another one further on, but the Kayapó would go there to mess with our people [the girls]; when we grew in number we moved further away, you could only get there by bicycle. A second group stayed in the town of Tucumã, close to Ourilândia, a third group lived in the Gorotire village and a fourth group lived in the town of Redenção. Later the decision was made for everyone to move to Tucumã. We built a house where we all stayed together. We then decided to go to live in Cajueiro village, since we had been told by Funai’s administrator in Altamira that the Curuá Indigenous Territory was reserved for the Kuruaya and the Xipaya and that there was a gold mine to be explored. We hired a bus to Altamira carrying ten families and joined the three families that were waiting there. We continued our journey to Cajueiro village in a boat called ‘Mão Divina,’ but when we arrived there we all came down with malaria and we returned to Altamira. That was in 1991. When we had recovered, some of our group stayed in Altamira while the remained managed to live for a year in Cajueiro. In 1993 we moved to the Iriri where we decided to fight for our own land. (Interview conducted in April 2000.)

The arrival on the Iriri river and the reorganization of the community marked a new moment in the life of the Xipaya. After two centuries of contact and forced migrations they managed to reconquer their former homeland. The first request made to Funai dates from 1995; the Working Group appointed to carry out the detailed identification and delimitation study conducted its field research in 1999.

The Xipaya in Altamira

The presence of the Xipaya in Altamira dates from the middle of the 18th century when the Jesuit priest Roque Hunderfund created the Tavaquara mission. In a forced migration he led various indigenous groups to populate the new settlement, including Xipaya, Kuruaya, Arara and Juruna. The mission faced difficulties in continuing after the Marquis of Pombal expelled the Jesuit missionaries from Brazil in the mid 18th century.

Records of the mission’s existence were left by Prince Adalbert of Prussia on the expeditions that he conducted on the Amazon and Xingu rivers between 1811 and 1873. The scientist Henry Coudreau, who undertook an expedition to the Xingu river in 1896, also mentions the mission’s location: "An extinct mission of the priests... based at the mouth of the Itaquari creek, a small affluent of the left shore [of the Xingu], longer but drier than the Panelas [creek].”

The older Xipaya recall that the mission, though short-lived, became an occupation site for the indigenous groups in question. Nearby the commercial centre formed of what would become the town of Altamira. In the 20th century the village was transformed into an urban neighbourhood known as Muquiço, due to the large number of brothels, bars, festivals and ‘arruaças’ located there. Afterwards the district became known as ‘Onça’ due to a shed where jaguars and wild cats where held captive for sale in the fur trade. Today the district is called São Sebastião in homage to the city’s Patron Saint.

The indigenous population slowly lost control of their territory as the distinct became absorbed by the town and there was a process of occupation by groups that traversed the Xingu-Iriri-Curuá region in order to work in rubber and Brazil nut extraction, as big cat hunters (capturing wild cats and jaguars to sell their fur) and as boat pilots. The women who remained in the town were employed as domestic workers, washerwomen and companions, especially the younger generation. During this period flu and measles epidemics decimated a large proportion of the indigenous population.

The second half of the 20th century was characterized by real estate expansion, responsible for plunging the Indians into debt since the ‘owners’ of the lands possessed land deeds at the regional land registry office. This period also saw the implementation of large-scale projects such as the Transamazonian highway, which brought a considerable number of migrants to the region and led to a profound change in the regional setting, which worked against the consolidation of an indigenous territory and the maintenance of social organization in the shape of a village.

A request for repossession of part of the territory was made to Funai and a Working Group was sent by the agency in June 2001 to collect basic information on the area claimed by the urban indigenous population of. The Xipaya leader who coordinates the Association of Indigenous Residents of Altamira (AIMA), along with the older generation who still speak their indigenous language, expressed the need for a space in the city to be set aside for the construction of a village. The request was sent to Funai in 2000. On June 26th 2001 a technical group was organized to conduct a Basic Survey of information on the indigenous lands. The final report suggested the constitution of a technical group to select an appropriate area. The prevision is that by the end of 2003 the Prior Study will be concluded by the anthropologist hired by Funai.

Social and political organization

The matriarch of the Xipaya group is married to a former 'rubber soldier.’ Their marriage resulted in 22 children of which just 16 are still alive. Tukamã village is formed by 13 of their children who established their own families and whose leadership passes from brother to brother, which does not mean there is a consensus when a member becomes leader.

Marriage is more often referred to by the term ‘gathering’ and the search for partners has been made among the Kuruaya and Mebengokre groups and the non-indigenous population. For the Xipaya, the village ensures the future of the children who live there in the sense of providing a guaranteed area to live whose future everyone is responsible for ensuring.

Three of the siblings live in the city. Their families were formed by marrying non-Indians and second-degree Xipaya cousins. A woman is the leader in the city and there the social organization of the families is constituted by small family nucleuses in different districts.

In Altamira indigenous urbanization has recently been discussed by FUNASA, SEDUC, SEMEC and CIMI, as well as by the anthropologists studying the region. The rise in the public profile of this issue is primarily due to the activism of the Xipaya and Kuruaya and the other indigenous groups living in the city, as part of their efforts to ensure that their rights as indigenous citizens are respected. It is also due to the creation of associations representing the two ethnic groups, including both those living in the village and those in the city. This has helped give them the visibility they lacked prior to 1998 since the literature identified them as extinct.

While at the start of the 20th century the distribution of the indigenous population was limited to what is today the district of São Sebastião, currently the indigenous population is distributed among the different districts of Altamira: Aparecida (18 families: 13.04%), Boa Esperança (15 families: 10.87%), Independente II (14 families: 10.14%), Brasília (10 families: 7.25%), Açaizal (8 families: 5.80%), São Sebastião (7 families: 5.07%), Recreio, Jardim Industrial, Independente I and Centro (6 families each: 4.35%). Some of them are recent and have a low-level of infrastructure. They are organized in nuclear families, the pattern of the society into which they were incorporated.

Environment and productive activities

The climate of the region where the Xipaya Indigenous Territory is located is equivalent to tropical forest with monsoon-like rainfall. The dry season is short-lasting with rainfall below 60mm in the driest month, though there is still enough humidity for the development of an exuberant forest vegetation. The temperature averages about 25ºC.

In terms of vegetation, the region is composed of different forest types:

- Open Mixed Tropical Forest (Cocal): formed by palms and broad-leafed trees with clusters of babassu and concentrations of small-leafed deciduous trees (plants that lose all their leaves during part of the year, generally in winter or during the dry season).

- Open Broad-leafed Tropical Forest (Cipoal): tree formations totally or partially covered by vines with similar woody vines in the flatter areas. The narrow valleys are occupied by babassu palms and broad slopes covered by vines.

- Dense Tropical Forest: present along the Iriri river, seasonally flooded, the area is dominated by ucuubatachi, kapok and possum wood.

- Second-Growth Forest (Capoeira): found around old and new settlements, derived from areas previously used as swiddens. This vegetation grows after the destruction of the forest in processes ranging from complete razing of the area for the implementation of agriculture to the selective removal of economically valuable trees.

Xipaya agriculture and livestock breeding are pursued in their swiddens and yards. The yards are found next to the houses where small livestock are raised and various medicinal plants, vegetables and fruit trees are planted. The fruit trees include cupuaçu, avocado, lemon, tangerine, annatto, sweet orange, orange, mango, jackfruit, jambo, bacaba, coffee, pineapple and papaya, as well as yams and sugar cane.

The families breed chickens and ducks for their own consumption and, where possible, for sale in local markets.

The swidden is a community task undertaken in the second-growth forest: in June/July the area chosen for the swidden is cleared; the thinner vegetation is cleared and the thicker trees felled with axes or chainsaws. From August to October the cleared or felled vegetation is burnt and the remaining timbers chopped. In November the felling continues, followed by another burning, the clearing of the terrain and the beginning of planting, which continues into December.

In terms of extractivism the Xipaya collect various plant products including: timber (used in the construction of houses and furniture), vines (for bindings and basketwork), medicinal plants, fruits and palm hearts. Craftwork production is focused on the manufacture of subsistence tools, including hunting weapons, household utensils and baskets. The soft clay – tabatinga – found on the river shores is used to line the wood stoves or house floors and to make tiles and bricks.

The Xipaya hunt with guns. The most common methods involve walking through the forest, lying in wait (hunting screens in the places frequented by prey) and using dogs, a frequent practice. Hunting may be practiced individually or in a group: in the former case the produce may be shared by the entire community if it is large, in the latter case the produce is shared by the group.

Hunting trips are always celebrated with festivals, the most famous being the one held on December 24th each year. After a month in the forest hunting tapir, tortoise or peccaries, the community reunites and makes a lot of food, inviting their neighbours for the festival as well as Kuruaya relatives. The preferred hunt game are deer, curassow, collared peccary, paca and above all the red brocket deer and other deer. Monkeys are not seen as good prey since they are thought to transmit diseases. River turtles are frequently eaten and are caught by diving in the rivers.

Fishing is considered a fundamental activity and is pursued throughout the year since the Iriri river is fairly abundant in fish. The most popular fish are those with scales, such as peacock bass, piranha, piau, white pacu, pacu caranã, matrinxã. Harmful fish that cause itching, such as the barbachato, are thrown back in the river. Other fish existing in the rivers are surubim, pirará, cat fish, sardinha and fidalgo. Both women and men fish. The most frequently used techniques are hook and line, called tela; caniço, using a fishing rod; machete; bow and arrow; and various forms of pasternoster line.

People sell rice, flour, chickens, maize, coconut oil, Brazil nuts and fish, but this produce does not always interest the regatões (river traders who ply the waterways, stopping at different localities). Today they possess their own boat and are no longer dependent on these intermediaries, allowing them to buy and sell produce in Altamira.

Prospects

The Xipaya today, after the endless migrations and uncertain residence sites, can now imagine a territory for the future of their children and their cultural reproduction. The Detailed Identification and Delimitation Report for the Xipaya Indigenous Territory was not contested. After the ruling of the President of Funai approving the document they are waiting for the Ministerial Decree from the Minister of Justice and the later publication of the public notice for demarcation. The creation of the Arikafu Association has been the official channel used by the Xipaya to engage with local society, government agencies and non-governmental bodies.

As for the situation of the urban Xipaya, their rights are gradually being achieved. The Association of Indigenous Residents of Altamira (AIMA) has helped raise the profile of issues that were once ignored. Today they deal with their problems directly with the institutions and Funasa has responded to these demands, as well as the incumbent local council, but a work program for improving their living conditions has yet to be developed. Funai, for its part, knew of the existence of the Xipaya in Altamira but ignored the fact. In the urban setting, their rights become mixed and confused with those of non-indigenous citizens. Recently the institution has responded to the issue with more attention.

Sources of information

- COUDREAU, Henri. Viagem ao Xingu. Belo Horizonte : Itatiaia ; São Paulo : Edusp, 1977.

- NIMUENDAJÚ, Curt. Fragmentos de religião e tradição dos índios Sipáia : contribuições ao conhecimento das tribos de índios da região do Xingu, Brasil Central. Religião e Sociedade, Rio de Janeiro : Tempo e Presença Ed. ; São Paulo : Cortez, n. 7, p.3-47, jul. 1981.

. Textos indigenistas : relatórios, monografias, cartas. São Paulo : Loyola, 1982. (Missão Aberta, 6)

. Tribes of the lower and middle Xingu river. In: STEWARD, Julian H. (Ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. v.3. Washington : Smithsonian Institute, 1948.

- PATRÍCIO, Marlinda Melo. Índios de verdade : o caso dos Xipaia e Curuaia. Belém : UFPA, 2000. 144 p. (Dissertação de Mestrado)

- SNETHLAGE, Emília. Die Indianerstämme am mittleren Xingu : im besonderen die Chipaya und Curuaya. Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie, Berlin : s.ed., n. 45, p. 395-9, 1910.

. A travessia entre o Xingu e o Tapajós. Manaus : Governo do Estado do Amazonas ; SEC, 2002. 72 p. (Documentos da Amazônia, 98)

. Zur Ethnographie der Chipaya and Curuaya. Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie, Berlin : s.ed., n. 42, 1910.

- STEINEN, Karl von den. O Brasil central : expedição em 1884 para a exploração do rio Xingu. Rio de Janeiro : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1942.

- VIEIRA, Maria Elisa Guedes. Relatório circunstanciado de identificação e delimitação da Terra Indígena Xipaya. Brasília : Funai, 2003.

- WILHERLAN, Adalbert Heinrich (Príncipe Adlaberto da Prússia). Brasil : Amazonas-Xingu 1811-1873. Belo Horizonte : Itatiaia, 1977.