Zuruahã

- Self-denomination

- Suruwaha

- Where they are How many

- AM 171 (Siasi/Sesai, 2014)

- Linguistic family

- Arawá

Living far from the main navigation routes on the middle Purus river, the Zuruahã maintained their cautious isolation until the end of the 1970s, when they were located by missionaries from the Prelacy of Lábrea, alerted to their existence by the reports of conflicts with sorveiros (latex extractors) who invaded the indigenous territory. A marked feature of this group is the high rate of suicide, intensely linked to their cosmological system and the territorial pressures seen over the last few decades (see chapter "Cosmology and suicide")

Language and identification

The Zuruahã speak a language of the Arawá family, which also includes the Jamamadi, Kanamanti, Jarawara, Banawa-Yafi, Deni, Paumari and Kulina. All the representatives of this linguistic family inhabit the region between the basins of the middle Purus and Juruá rivers, two large affluents of the right shore of the Solimões (upper Amazon).

Following the initial contacts with members of CIMI (Indigenist Missionary Council), they became known as ‘Indians of the Coxodoá,’ the name of the creek where they were encountered. The ethnonym by which they are now known was actually taken from an extinct subgroup – the Zuruahã of the shores of the Cuniuá, celebrated shamans. While it was initially no more than a device to satisfy the insistent curiosity of the indigenists, it quickly became an established expression among themselves too. But there are still a number of people who stubbornly refused this ethnonym with the decisive argument that there everyone would be Jokihidawa, since they are all now living on the lands of the Jokihi creek.

Location and population

The Zuruahã live in upland region between the Riozinho and Coxodoá creeks, affluents of the right shore of the Cuniuá. Flowing eastwards, the latter is one of the headwaters of the Tapauá river, an important tributary of the left bank of the Purus (Amazonas state, Brazil).

The Zuruahã Indigenous Land was ratified on 29/10/1991 (dec. 266), covering an area of 239,070 hectares. It forms a typical ‘terra firme’ zone, irrigated by small rivers that increase in volume each year during the rainy season from November to April and flood the lakes and igapós (marshy forests) that dot an otherwise relatively uniform topography. In January 1996, the Zuruahã numbered 144 people. Despite the setbacks some years, their population has been growing slowly since 1980 when they were slightly more than one hundred in number.

History

The Zuruahã say – and for this we have other historical evidence (Barros 1930) – that they are remnants of various named territorial subgroups whose populations, succumbing to infectious and contagious diseases and the cruelty of the rubber economy – declined drastically in the first decades of the 20th century during the boom in extractivist activities throughout Amazonia. The most cited subgroups in the Zuruahã historical narratives are: the Jokihidawa on the Pretão creek, the Tabosorodawa on the Watanaha creek (and affluent of the Pretão), the Adamidawa on the Pretinho creek, the Nakydanidawa on the Índio creek, the Sarakoadawa on the Coxodoá creek, the Yjanamymady on the headwaters of the São Luiz creek, the Zuruahã on the Cuniuá river, the Korobidawa on an affluent of the left shore of the Cuniuá, the Masanidawa at the mouth of the Riozinho, the Ydahidawa on the Arigó creek (an affluent of the Riozinho) and the Zamadawa on the upper Riozinho.

Some subgroups, including the Masanidawa and the ancient Zuruahã, formed friendly relations with the rubber tappers (the Jara, as the ‘civilizados,’ or ‘civilized people,’ are called) and were therefore able to obtain clothing and tools – axes, machetes, hooks and ropes that soon became exchange objects with the other subgroups. However, decimated by flu viruses (the SPI worker José Sant'Anna de Barros recorded epidemics in the Tapauá basin between 1922 and 1924, with a high death rate among the indigenous population, cf. Barros 1930:11) and withdrawing from the new attacks launched by the Abamady (probably the Paumari of the lower Tapauá, armed with shotguns supplied by the rubber bosses), a few survivors from different subgroups sought refuge on the banks of the Jokihi creek (called the Pretão by the regional population), the furthest distance possible from the fluvial routes and the ‘colocações’ (dwellings) of the new arrivals. Here they joined the Jokihidawa (literally, ‘the people of the Jokihi’), the subgroup that had originally resided there.

Official contact

Funai had already been aware of the existence of the group since the mid 1970s. In December 1983 they were officially contacted by an agency expedition dubbed ‘Operation Coxodoá,’ composed of 12 people, including Waiwai and Waimiri-Atroari Indians. The expedition located eight malocas on the Índio and Preto creeks, both affluents of the Cuniuá river.

Before this, in 1978, they had already entered into contact with members of CIMI (Indigenist Missionary Council) based in the Prelacy of Lábrea, who had visited them fairly regularly over subsequent years.

They also began to have contact with members of the JOCUM mission (Jovens com uma Missão, an organization apparently linked to the Summer Institute of Linguistics) from July 1984 onwards, who exploited the channel opened by the FUNAI expedition to approach the group.

Also in 1984, the workgroup for identification of the area was set up (Directive No. 1764/E of 14/09/84) which included member of FUNAI and the Prelacy of Lábrea. In 1985 an area of 233,900 ha was proposed in the recently created municipality of Camaruã. The report indicated that the malocas were located between the Pretão and Riozinho creeks, suggesting a desire to be as far as possible from the Cuniá river where the presence of whites was more frequent. The workgroup noted that the delimited territory was being invaded by a wave of extractivists, formed mainly of sorveiros and rubber tappers.

The Zuruaha Project, still active today, began to be developed in 1984 precisely to combat the adverse effects of these waves of non-indigenous occupation. The program focuses on welfare initiatives, defence of the Indigenous Territory, and disease treatment and prevention, run by a team formed by members of OPAN (Operação Amazônia Nativa), CIMI and the Prelacy of Lábrea. The Zuruahã also receive the help of psychologist Mário Lúcio da Silva, who has been living among them for a number of years.

Social organization

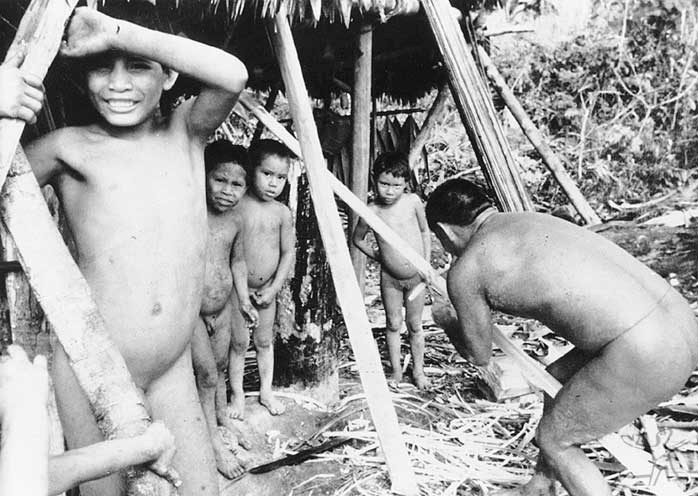

For most of the year, the Zuruahã live as a group in one of the large conical houses built in the centre of their territory. Social life develops within this shared dwelling in a complex web of kinship relations, friendships and multiple forms of co-existence.

In the house (oda) without side walls or internal dividing walls, each family occupies more or less randomly (where possible, close to the consanguine kin of one of the spouses) one of the domestic areas (kaho) distributed throughout the architectural space. The house belongs to the man who built it: he is the 'owner' (anidawa) and makes the necessary repairs when the group resides there – a period varying from some months to a little over a year.

Building houses is one of the attributes of male adulthood; over his lifespan, a man will build four or five of them. For their construction, which requires one or two years of dedication and much effort, all the men collaborate in assembling the wooden structure, while the covering of thatch falls to its anidawa.

As well as ‘house owner,’ the anidawa category covers other relations, such as swidden ownership, the possession of valuable objects (a canoe, for example) and leadership of collective hunting and fishing trips. In each case, it corresponds to certain rights and duties that guide the course of social action.

Social units

Although doubts persist concerning the rules of belonging and other general aspects, ethnographic descriptions are unanimous in mentioning the existence of multiple local units, subject to successive splits and migrations due to internal conflicts or classes with analogous groups and strangers. Within this setting, violence and sorcery accusations simultaneously express mutual distrust, failed exchanges and the attribution of blame following sickness and death.

For the Zuruahã, these types of unit are designated by the following terms: dawa, a term almost exclusively restricted to their own subgroups; and mady, whose meaning is more or less inclusive, depending on the context (persons, relatives, groups, peoples, humans). Available evidence suggests that geographic features or other local features served as an eponym to designate the subgroup occupying the territory in question. References to the sites inhabited by the subgroups or their members appear in narratives on past wars, sorcery attacks and migrations, including those describing the events that culminated in their unification seven or eight decades ago (Fank & Porta 1996b).

The current somewhat imprecise use of these designations also seems to translate a particular residential inclination, insofar as it rests on closer ties with either paternal or maternal kin, or with both. Children born outside matrimony (including in the case of widows) are denied affiliation to any of the subgroups.

Kinship

The opposition between consanguines and affines, which is ritually expressed at the moment of male initiation (sokoady), corresponds to a clear conceptual distinction in the domain of kinship on which the typically Dravidian terminology generates a positive rule of cross-cousin marriage in the central generations. However, in detriment to kinship nomenclature, in their everyday lives the Zuruahã usually prefer to use proper names or various kinds of teknonyms. Likewise, a somewhat unusual genealogical memory, reaching back five or more generations, particularly emphasizes names and nicknames – which are rarely repeated – and various colourful details from a long line of ancestors. This would seem to indicate a system that essentially focuses on individuals and particularizes them in line with a number of personal features selected from a predefined catalogue (name, physical attributes, temperament, skills, etc.).

Leadership and gender

Whether in routine activities or critical situations, no kind of institutionalized leadership or political centrality has so far been observed. On this point, the group’s social organization seems to distance itself from the other Arawá, among whom leadership is a key function (for example, the tamine among the Kulina). In its place, though, the Zuruahã possess a kind of ‘order of hunters,’ hierarchical in nature, which ranks men according to the number of tapirs each one has killed.

A strong opposition differentiates men and women, attributing unequal value to the two sexes in many aspects of social life. For both sexes, male children are a legitimate source of pride, meaning that the demand to have them is sometimes almost equivalent to a moral obligation from which not even outsiders escape. Indeed, one of the spells most feared by women is precisely that they will be prevented from conceiving boys. Furthermore the very social recognition of an individual’s biological maturation – that is, the transition to the dogoawy age classes – is based on the parameter of the life cycle of male descendents.

Life cycle

Following early childhood, the Zuruahã age groups are divided into six basic phases:

| Phase | approximate age | Men | Women |

| 2 to 7 anos | 2 to 7 | hawini | hazamoni |

| from 8 to sokwady/ menarche | 8 to 13 | kahamy | zamosini |

| to adolescence of child | 14 to 28 | wasi | atona |

| to birth of grandchild | 29 to 38 | dogoawy | wasi dogoawy |

| to adolescence of grandchild | 39 to 52 | dogoawy | dogoawy |

| white hair | 53 above | hosa | hosa |

Ceremonial life

In the ritual sphere, male maturity (between 12 and 14 years old) is signalled by fitting of the sokoady (a penile ‘suspender’), a public event that essentially thematizes the relations of affinity (with whom a person may marry). After a large hunting or fishing trip, collectives meals and dancing, the boys receive the adornment of cotton strings and are then thrashed by the adult men (apart from their consanguine kin). Then they go to lie in hammocks suspended high up in the central part of the house, while their consanguine relatives take part in a fight against the other men (the latter, decorated, gesticulate like ‘woolly monkeys,’ which provides the name for this ritual duel: gaha), embracing them strongly from behind. In the final stage, the boys are taken by the women to bathe in the river, where they cut their hair and paint them with annatto; while bathing, the onlookers make joking insinuation about the initiate’s future sexual relations (Fank & Porta 1996a:14-20).

For girls, the entry into adolescence on the arrival of the first menses involves their reclusion and isolation in the core of domestic space (with her eyes blindfolded, the girl remains lying in her hammocks, almost without eating and only usually leaves the house at night to satisfy her biological needs). But it is in the effective control of female sexuality that, strictly speaking, gender differences are reiterated and the forced submission of women becomes evident: their sexual behaviour is under constant surveillance, there are frequently chastized by their parents, brothers or other close kin and are barred from leaving the house unaccompanied due to the threat of ‘sexual abuse’ from non-consanguines.

At various moments and in various ways, personal virtues and individual performance are evoked, highlighted and socially valorized. Juvenile vigour is constantly and ostentatiously exalted and displays of physical strength occur frequently — especially during the house building work – sometimes even involving men of an advanced age. Likewise, in the ‘carrying rituals,’ men and boys, one by one, are obliged to transport a voluminous bundle of sugarcane or a large basket stuffed with grated manioc pulp. In the domain of moral and aesthetic judgments, it may be possible to infer a very similar kind of individualization through polite or cruel comments concerning other people’s behaviour, remarks on the physical similarities between individuals, praise for all kinds of qualities and even bizarre parts of the human anatomy (the calves, for example).

Cosmology and suicide

One of the most pronounced and dramatic aspects of Zuruahã society is the high incidence of voluntary death through the ingestion of konaha (timbó, a plant variety widely used to poison fish among South American indigenous groups). Between 1980 and 1995 there were around 38 deaths by suicide among the Zuruahã — 18 men and 20 women — amid an average population of 123.6 people. Over the same period, 101 children were born and 66 people died in total. On one hand, therefore, a high birth rate (around 6.3 births annually) and on the other, a fairly low demographic growth rate of around 1.9% per year. Mortality factors were dominated by the intense practice of suicide by poisoning (38 cases, or 57.6% of the total). Among the adult population (people over 12 years old) during the same period, suicides accounted for an extraordinary 84.4% of all deaths in this age group (38 cases from a total of 45).

In a genealogical survey extending over the previous five or six generations, 122 cases (75 men and 47 women) were reported prior to 1980. Whatever the period in question, however, we can note that most of the suicides involved young people of both sexes (in other words, individuals in the wasi and atona age groups, comprising young men and women, respectively, between 14 and 28 years old).

The high suicide rate among young people does not cause any surprise to the Zuruahã themselves. They share the firm opinion that “wasi and atona like drinking konaha; not dogoawy” (mature men and women), as Ohozyi declared frankly. This tendency in fact reveals various premises rooted in the indigenous philosophy of life, which attribute an absolute value to this stage of the biological cycle and, as a corollary, a resolute denial (and a certain disdain) for old age and physical decline. According to the Zuruahã, for this reason “it’s not good to die old, it’s good to die young and strong.” Consequently, the orientation and values that exalt youthfulness and inform their radical conduct are entirely congruent with the suicide rates.

Among the Zuruahã, young people of both sexes go through a fairly turbulent period in their relations with the family and the collective, a period that begins soon after the events marking his or her distinct entry into adult life – in other words, the imposition of the sokoady for boys and the first menstruation for girls – and that continues throughout the first years of their marriage — the conjugal misunderstandings and the tense co-existence with affines, indeed, make up an explosive mixture. The exceptional emphasis placed by Zuruahã society on physical and moral virtues, especially those connoting youthfulness, seems to account for most of the disruptive tensions afflicting young men and women, who face intense pressure in terms of their individual attributes (physical strength, ability, disposition, beauty, control of sexuality, etc.) and are therefore particularly prone to quarrels and dislikes. These conflicts seem to wane with the birth of the first children, when the couples finally achieve a degree of emotional stability (Fank & Porta 1996a:6).

A death foretold

Most suicide attempts follow a fairly regular pattern of behaviour. Poisoning, or intoxication, which the Zuruahã call konaha bahi, “because of the timbó,” is the only means used for this purpose. Meanwhile the path taken by the suicidal person – customary and predictable in some situations – can be decomposed into a series of typical moments:

- a specific event provokes irritation or annoyance;

- the individual then destroys his or her belongings (cuts and burns his or her hammock, destroys weapons and/or tools, smashes pottery utensils);

- the onlookers, kin or otherwise, allow the person to let out his or her aggressiveness; they try to conceal the fact they are observing and, with studied naturalness, carry on with their routine activities or immediately begin a task; they avoid looking directly at the angry person, but furtively track his or her movements;

- if this catharsis has failed to dispel the anger or displeasure, the individual will let out a cry or leave the house ostentatiously, running towards a swidden to pull up the timbó roots;

- those who had been watching discretely advise everyone else (kin, perhaps) and some people (usually of the same sex) pursue the suicidal person or, if the latter is already some distance away, search for him or her along the trails leading to the swiddens;

- if the pursuers find the person, they try to take the roots off him or her; otherwise, the suicidal person heads to a stream and there squeezes and chews the timbó to ingest its juice; he or she then drinks some water to activate its toxic effects;

- then, he or she runs back to the house (some fail to arrive, fainting or dying on the path);

- arriving home, the person is cared for by his or her kin or other people, depending on the motives and the relations that provoked the suicide attempt; saving the person’s life involves provoking vomiting, irritating the oesophagus with pineapple leaf stalks, heating the body with warmed fans (a task performed by women), striking the numb limbs, shouting in the ears and keeping the person sat upright at all times;

- during the course of the treatment, people generally express their anger with the suicidal person, talking to him or her aggressively and hurling insults;

- the death of the person, however, causes a strong commotion and acquires ritual expression through chanted wailing; the dramatic conclusion provokes other people (consanguines, affines, friends) to make new suicide attempts, either immediately or a few hours or days later, which lead to a new cycle of chases and attempts to save lives.

The physiological symptoms and reactions to timbó poisoning, such as low blood pressure, coldness, convulsions and swelling, are gradual and inspire varying degrees of care. The patient’s survival, however, depends on a variety of circumstances, including the person's resolve, the amount ingested, the resistance to treatment, the availability of people capable of helping him or her and the number of simultaneous attempts under way.

The motives that generally make an individual upset with someone else, with the group as a whole or with him or herself, or which affect the person in some way and which are given as justifications for suicide attempts, are entwined in a web of feelings that comes to the fore in these specific situations: these feelings include affection (kahy), anger (zawari), nostalgia (kamonini), especially in the form of yearning for the dead, and shame (kahkomy). During funeral rites, anger and longing are roused in relatives and friends alike and are fundamental to the expressions of mourning in this cultural universe.

The tragic death of a suicide invariably provokes numerous other attempts in a chain reaction that affects linear and collateral kin, affines and even friends of the victim. In fact, the same happens in any case of death, whether due to snake bite, illness or accident. This makes the funeral rites an immense drama, difficult to describe, that results in clashes between potential suicides and those trying to save them, imputations of blame, threats and even physical aggression. Consequently a person’s death almost always leads to a series of other deaths. In 1985, after the suicide of a young woman expelled by her mother-in-law, both her sister and sister-in-law died. In 1986, the suicide of a man, revolted with his wife who refused to prepare food for him, provoked the death of a friend and the latter’s classificatory father. In 1987, the mother and friend of a young man died after he had killed himself because others had complained about the excreta left by his dog. The same year, two adolescent girls drank konaha because their grandmother had scolded them for sexual lapses, which also led to the death of their brother. In 1989, when a girl died from a snake bite, her widowed father and the latter's two nephews – a 14 year old boy and a married man – all killed themselves. Three months later, the latter’s widow, her sister and the father of the boy also died. Two weeks later, the sister of one of the men who had died earlier had a fight with her husband and killed herself, accompanied by an adolescent girl. In 1992, a ‘house owner,’ fed up with the upkeep of the maloca, upset with his wife and annoyed by the disappearance of a knife, killed himself, accompanied by two of his brothers, their father and a man from his peer group. Finally, I learnt about a series of suicides at the end of 1996, caused by the death of a recently initiated boy, bitten by a snake in the hunt camp: two women (one being the boy’s mother), two married men and two single young women killed themselves.

Death in the cosmological complex

One of the key aspects of this question undoubtedly relates to the place of voluntary death in the Zuruahã cosmological model. All living beings are endowed with a mystical vital principle, the karoji. The karoji of human beings is the ‘soul’ itself, asoma. And the soul, to a certain extent, merges with the 'heart,' giyzoboni, the seat of memories, emotions and feelings, the true interior. One day Ody said to me: “You don’t speak, your heart does!” When someone dies, their heart/soul abandons him or her and, in the deepest waters of the creeks awaits the arrival of the rains; it then travels down the big rivers and jumps to dive into the sky (Fank & Porta 1996a; 1996b).

According to Gunter Kroemer (1994:150-1), the Zuruahã conceive of three distinct paths that cross the firmament: the mazaro agi (‘path of death’), the course taken by the sun and followed by those who die of old age; the konaha agi (‘path of timbó’), the trajectory taken by the moon and followed by those who commit suicide; and the koiri agiri (‘path of the snake’), the outline of the rainbow and the route taken by those who die of snake bites. As a result, the person’s eschatological fate is polarized between the house of the ancestor Bai, Thunder, in the upper celestial layer, for those who ingest poison and where ‘souls’ (asoma) re-encounter their kin and live as the authentic Konahamady (the ‘people of the timbó’), and the dwelling place of the ancestor Tiwijo, to the east, where the souls who die of old age travel. Those who have been killed by snakes remain in an intermediary space, the rainbow itself. Paradoxically, the journey to Tiwijo’s abode, conceived as a ‘painful path where the hearts wander without finding peace and quiet” (ibid:78), enables the soul’s transformation into an eternally youthful being. The source of this youth, people say, is a ‘sweet food’ which the souls receive on arrival — the old age rots in the grave along with the corpse’s skin. There life is good, crops grow effortlessly and hunting and fishing are abundant (Fank & Porta 1996a; 1996b). But according to Kroemer (ibid:78), it is towards Bai that the Zuruahã project their “true existence to which rites, songs and prayers are related” — a world engulfed by water where the souls eat only timbó roots and transform into fish, their final destiny (Fank & Porta 1996b:183-5).

Suicides or suicide attempts are basically provoked, then, by conflicts and crises that – in no particular order of importance – involve questions of ownership (tools, swiddens), the control over female sexuality, personal self-esteem (offences, illnesses, ugliness, failures), matrimonial alliance (marriage and conjugal relations) and above all the deep feeling that unites the living with dead kin. As a result, a kind of mortuary economy governs Zuruahã society, insofar as the dead are the ones who at a wider level produce the new dead through the suicidal response to mourning and sadness. The suicidal person, with his or her reckless attitude, is located in a dispute that can be glossed as a tug-of-war between the living and the dead. The latter ‘pull’ the person to accompany them in the beyond, a movement induced by the feeling of immediate grief or by the longing that returns later in memories and dreams. The former desperately try to save the suicidal person, an occasion when they express their rage with the one trying to abandon them.

In certain situations, the decisions to consume konaha corresponds to a form of self-punishment when the suicide assumes responsibility for inflicting harm on someone else. Here we can draw an analogy with the habit of consuming rapé (snuff), a favourite Zuruahã pastime. Assuming the blame for something, an individual may decide to take a pinch of snuff, or may be forced to do so by other people irritated by their troublesome conduct.

The shamanic model versus the suicidal model

A mode of homicide through sorcery — termed mazaro bahi, “because of death” — apparently existed among the Zuruahã in the past. The genealogical records contain 13 deaths from sorcery (nine men and four women), the most recent of which must have occurred between the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s. Moreover, in the accounts of the feats of their great shamans, the theme is very often associated with quarrels between people belonging to different subgroups. For example, people say that Aga of the Masanidawa ate a bat bewitched by Birikahowy of the Jokihidawa. Angered by the marriage of the latter to a Masanidawa woman, Aga squeezed him too hard in the gaha fight. Badly hurt, Birikahowy still managed to take revenge and both died in the same instant (Fank & Porta 1996b:55-6).

From a chronological perspective, though, this causa mortis has become rarer since the 1960s (and with it the iniwa hixa, the great shamans), in parallel to the rise in death by suicide. Despite their dangerousness, the Zuruahã lament the absence of their iniwa hixa, whose exceptional power allowed them to travel to distant places, destroy their enemies and even visit the realm of the dead. The two or three men to whom they attribute shamanic qualities are, people say, merely iniwa hosokoni, weak shamans whose activities are limited to making contact with the korime spirits, who teach them songs and bring news of distant places (1996a:37-8).

Until the first decades of the 20th century, the ancestors of the Zuruahã were organized in various local groups, settled in their own distinct territories, whose disputes – particularly when involving outsiders – required the intervention of sorcerers/shamans. Consequently, illnesses and death were attributed to malevolent action of the latter and their capacity to control mazaro bahi (sorcery). Today, though, there is just a single social and territorial unit and suicide appears as the most important cause of death. As a result, in the course of the changes occurring in the settlement pattern and in the field of relations with the exterior, something unexpected happened.

The unification of the survivors from the different subgroups had the immediate effect of concentrating and intensifying social life (interactions, duties, quarrels), but also led to a form of closure that instituted a mode of social life ‘among others’ – that is, full of surprises and risks. Danger almost always comes from the outside and the Others, but in this case, those outside are inside and the Others are one’s neighbours in the kaho (house).

There may well have be a genuine correlation between the previous social configuration, formed by multiple local groups, and the exercise of shamanic activities, on one hand, and between today’s single grouping and the suicidal acts, on the other. In the first configuration, the power of the shamans comprised an ‘interlocal’ form of mediation developed through the devices of splitting and opposition that linked and thus totalized the different collectives. In the second configuration, an analogous operation occurs, but at an internal level, insofar as the latent threat of suicide regulates interpersonal relations and opposes people. In this new setting, sorcery becomes a logical impossibility: hence the weakening of the sorcerers, since they and their art no longer have a place in a unified and –whether by principle or choice – a now indivisible collective. On the other hand, suicide can in some ways be seen as a variant form of sorcery, since there are indications of a symbolic association between them: as Ohozyi explained, the karoji (mystical vital principle) of the timbó “is a shaman,” explaining its power to seize possession of human hearts (Fank & Porta 1996b:182-7).

Hence, at one level of social life, the Zuruahã seem to act as though they form a fairly homogenous and strongly integrated whole. Activities such as building the house, the timbó fishing expeditions, the collective hunts, the ceremony for distributing tapir meat, the nocturnal snuff rounds and male initiation, as well as the incessant efforts to ensure that all the families can live in a single village — even if, at certain times, there are other houses also in a condition to be used — manifest, each in its own way, a pervasive spirit of social cohesion. The mere idea of someone remaining alone at night in some place outside the village provokes panic among friends and relatives. This fear is pervasive and continually renewed, since people never tire of speculating on potential attacks from outside society (zamady spirits, hostile indigenous groups, sorveiros). The fear of confrontations with these forms of alterity is, indeed, one of the reasons why the Zuruahã themselves have opted to remain isolated in their current area for more than six decades, practically confined in a small portion of their original territory.

Despite this model of unity and cohesion, though, the recurrent use of konaha emerges as a counterpoint in which an intermittent but assiduous social division is produced, mediated through suicide. In contrast, though, to the (unthinkable, for the Zuruahã) fragmentation and opposition between the parts, this operation interiorizes and propagates dissension within the limits of the local group, distinguishing the most elementary components of the social structure. Thereafter, every act and discourse is conditioned by what we could call the suicidal potential — the measure of efficacy and the parameter of value with which people calculate the probability of causing annoyances or harm to oneself and others.

Hence, in a suggestive self-image, the Zuruahã sometimes reflect on their similarity to fish, both victims of timbó. In these terms, it is the society as a whole that is projected through a recognizedly individualizing gesture (one attempt is enough!): a suicide that is precipitated in the epicentre of social action, a focal point to which actors, positions and relations converge, according to a system of standardized attitudes and values. With each suicide attempt, the individuals occupy or swap their respective positions, looking to respond to both their kinship and personal relations and their commitments within the particular social setting.

Suicidal behaviour among the Zuruahã does not amount, therefore, to a disorder or dysfunction, much less a form of deviant conduct. Instead it implies specific structural principles that singularize the social body, namely: the opposition between the living and the dead, where the suicide attempts involve the relation between a dead person and, in the act of saving the victim, the task of the living to look after the suicidal person; the asymmetry between consanguines and affines, with an emphasis on the ties of descent and siblinghood; the age group dynamic, which distinguishes young and old, in particular in terms of the posthumous fate; social status, which may lead to a greater indifference or an increase in the number of potential suicides; and the confrontation between the sexes, which is exacerbated on these occasions. In sum, this set of factors allows us to argue that suicide firmly installs difference within society, at the same time as it totalizes it – at the expense, though, of a notably individualizing ritual act.

Productive activities

As well as the daily solitary excursions along the trails that radiate out from the village, Zuruahã hunters undertake two larger forms of hunting expedition: kazabo, a camp-based mode that includes the participation of nuclear families and lasts for weeks, and zawada, involving men only who travel to more remote areas for a week or a little longer.

The Zuruahã use basically one type of curare for hunting, smeared on their arrows and blowgun darts. In fishing, as well as hooks and nylon lines, they make use of plant poisons and organize collective fishing trips. Towards this end, they cultivate a variety of timbó (konaha, probably a legume of the lonchocarpus genus, whose main active compound is rotenone) and a variety of tingui (bakyma).

The game par excellence is tapir, whose kill results in an elaborate ceremony of cooking and distribution. As well as the prestige that they invariably acquire, the best hunters have primacy in sharing out the meat, where they hunting rank determines, wherever possible, their place in the sequence of distribution and the portion they will receive.

In terms of agriculture, the Zuruahã swiddens are varied and extensive, mostly planted with varieties of bitter and sweet manioc, sugarcane, banana and root crops. An immense variety of wild fruits are gathered throughout the year, complementing the plentiful list of foods.

Sources of information

- BARROS, J. S. A. Relatório da viagem de fiscalização ao rio Tapauá e seus afluentes, apresentado ao Inspetor do SPI no Amazonas e Acre, mimeo., fotos, 21 p., Museu do Índio/Sedoc, Filme 31, Planilha 380, 1930.

- CIMI (Conselho Indigenista Missionário). A violência contra os povos indígenas no Brasil: 1994-1995. Brasília : Cimi, 1996.

- DAL POZ NETO, João. Crônica de uma morte anunciada : do suicídio entre os Sorowaha. Rev. de Antropologia, São Paulo : USP, v. 43, n. 1, p. 89-144, 2000.

- FANK, J. & PORTA, E. A vida social e econômica dos Sorowaha. Cuiabá : OPAN/CIMI. 1996a.

- -------. Mitos e histórias dos Sorowaha. Cuiabá, OPAN/CIMI, 1996 b.

- -------. Vocabulário da língua Sorowaha. Cuiabá, OPAN/CIMI, 1996 c.

- KROEMER, Günter. A caminho das malocas Zuruahá. São Paulo : Loyola, 1991.

- -------. Cuxiuara, o Purus dos indígenas. São Paulo : Loyola. 1985.

- --------. Kunahã made, o povo do veneno : sociedade e cultura do povo Zuruahá. Belém : Mensageiro, 1994. 207 p. (Coleção Antropologia)

- O povo do veneno. Dir.: Júlio Azcarate. Vídeo Cor, VHS, 25 min., 1991. Prod.: Ibase Vídeo; Cimi; UBV

- SILVA, M. L. da. Um estudo sobre a sociedade suruwaha. Mimeo, 1994a.

- -------. O drama de Xibiri-wiwi. Mimeo, 1994 b.

- SUZUKI, M. "Esboço preliminar da fonologia Suruwahá". In : WETZELS, L. (org.), Estudos fonológicos das línguas indígenas brasileiras. Rio de Janeiro : Ed. UFRJ, 1995. pp. 341-78.

VIDEOS